Last year, a cheesy made-for-TV movie called Sharknado achieved a level of fame far out of proportion to its merits. In this joyously inane motion picture, an unexpected hurricane – the worst kind – churns up the waters off the southern California coast and starts depositing man-eating sharks – the worst kind – on to the streets of Los Angeles, making rush-hour traffic even more maddening than usual. Oddly, in a jarring lapse of authenticity and narrative cohesion, no other species of fish get involved. Nor are there any whales or dolphins or octopuses or seals or walruses flying through the Santa Monica air. It’s Sharknado, not Squidnado.

The sharks, to their credit, do not seem all that surprised to find themselves thrashing about on the northbound lane of the freeway or swimming around people’s living rooms. They do what sharks always do; they put on their game face and start noshing. Predictable mayhem ensues as battle-tested beach police and one feisty, bikini-clad waitress teach the airborne tigers of the deep not to bite off more than they can chew. Sundered families are reunited, young love is kindled, addled drunks demonstrate guts one would not have expected in such jaded burnouts, and sharks, as usual, meet their match – largely because humans have access to helicopters and explosives and science, which sharks do not. Humanity, as the saying goes, takes a licking, but it keeps on ticking. The explosives really helped; without them, the City of Angels would have been toast.

Kelly Osbourne: set to play a flight attendant in Sharknado 2. Photograph: Christopher Polk/AMA2013/Getty Images

Kelly Osbourne: set to play a flight attendant in Sharknado 2. Photograph: Christopher Polk/AMA2013/Getty Images

Sharknado did not garner eye-popping ratings when it first aired on the science-fiction channel that commissioned it – in part because America is a shark-saturated society – nor did it perform especially well during its microscopic commercial release period. But over the following months, particularly after irony-minded people such as Olivia Wilde started tweeting about it, the film built momentum and gradually achieved a cult-like stature. It was the kind of film that kept turning up on Netflix (“Based on your interest in Bambi and La Grande Illusion and Some Like It Hot, we thought you might like Sharknado”) – and had the unusual distinction of being talked about non-stop by people who had not actually seen it and probably had no intention of doing so in the future. In this sense it resembled Finnegans Wake or A Brief History of Time. Most people probably figured that a film with a title that self-explanatory – not unlike Snakes on a Plane – did not actually need to be seen to be appreciated. But in this they were utterly wrong.

For a number of reasons, Sharknado is a very special film. Incredibly stupid movies about sharks are a dime a dozen, but Sharknado has that little extra something, what the French call the je ne sais quoi, mais moi je trouve les requins formidables quality. For one, it sports a fabulously goofy name, one that tells you just about everything you could possibly need to know about where the film is headed. This is only to be expected from a movie whose screenwriter boasts such previous credits as Mutant Vampire Zombies from the ‘Hood!

Snakes on a Plane: the title says it all. Photograph: c.New Line/Everett/Rex Features

Snakes on a Plane: the title says it all. Photograph: c.New Line/Everett/Rex Features

But Sharknado also has something that a lot of knowingly idiotic movies do not have: a kind of amiable earnestness. Unlike such self-consciously ironic films as Norwegian Ninja or Cheerleader Ninjas or Strippers Vs Werewolves or The Legend of Awesomest Maximus, films that are fully aware of their own ridiculousness, Sharknado stands out because of its bewitching sincerity. The characters inhabiting Sharknado do not seem to be aware that sharks can’t fly. Or, if they do know it, they keep it to themselves. The cast, consisting of a bunch of failed nobodies and would-be has-beens, one of whom only took the job because he needed health insurance for his family, do not play the material for laughs. They go about their business of dispatching the sharks with genuine enthusiasm and ingenuity. And, in a few instances, real panache.

Like the stars of all classic B-movies, the characters in Sharknado do not act as if the idea of a tornado depositing sharks on the freeway is far-fetched or funny or even especially unrealistic. Sharknado has no nudge-nudge, wink-wink quality to it. Sharknado, like Planet of the Apes or The Swarm or Orca or Godzilla, accepts its absurd premise on its own terms, and then plays it as it lays. Nobody hams it up. Nobody mugs. Nobody acts like this is some big, stupid joke. Everybody acts as if they were making Citizen Kane or Gone with the Wind, or, for that matter, Jaws. The way the protagonists see it, there are big, nasty, bloodthirsty sharks chomping on beleaguered senior citizens in the nursing homes of Beverly Hills, and nasty sharks threatening to devour entire school buses – the way their species once took down a helicopter in Jaws 2 – and it’s their job to get rid of them. So they roll up their sleeves and get on with it.

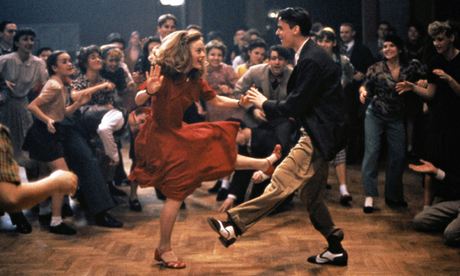

Swing Kids: jitterbugging v the Third Reich. Photograph: Allstar/Hollywood Pictures/Sportsphoto Ltd/Allstar

Swing Kids: jitterbugging v the Third Reich. Photograph: Allstar/Hollywood Pictures/Sportsphoto Ltd/Allstar

The original Sharknado experience was loads of fun. Then, just like that, the fun evaporated. Matt Lauer, one of America’s most famous morning talkshow personalities, and Al Roker, his beloved weatherman sidekick, announced that they would be appearing in the sequelto the film. Then it was disclosed that suchhigh-profile B-list celebrities as Kelly Osbourne, Andy Dick and Judd Hirsch would be joining the cast. Meanwhile, the film’s producers divulged plans to raise $50,000 through crowdfunding to shoot a spectacularly idiotic scene involving chainsaws. The original Sharknado, for the record, has a spectacularly idiotic scene involving chainsaws, one that would be hard to top. From the comic perspective, it may be the best impromptu chainsaw work since Scarface. Seriously. So even if you aren’t a fan of stupid shark movies, Sharknado is worth watching just for that final scene where one particularly aggressive shark gets exactly what’s coming to him – thanks to a chainsaw that turns up in a completely unexpected place. It’s hard to imagine how the sequel could possibly improve upon this scene. No matter how much money the producers raise.

Films like Sharknado are fun precisely because they are not ironic, not camp, not cunningly orchestrated. What makes a stupid movie great is that the people in it don’t know how stupid it is. In this sense, Sharknado resembles Swing Kids, where a bunch of peppy jazz aficionados living in Nazi Germany try to fight the Third Reich by jitterbugging it into oblivion. Films like this proceed from such a ridiculous premise that you wonder how they ever got greenlit in the first place. The very fact that they exist is life-affirming in and of itself, driving home the reassuring truth that on this planet, in this solar system, in this century, anything is possible. Even a film about sharks dumped on to the streets of Los Angeles by a tornado. Or a hurricane. Or a bunch of malignant water spouts. Or something.

But as soon as ubiquitous, overexposed personalities such as Matt Lauer and Al Roker and Kelly Osbourne announce that they want to be in the Sharknado sequel, the magic fizzles out. It’s like when hipsters discovered The Sopranos: oh no, not you again! Films like Sharknado should come with a warning: attention, famous people – hands off our film. That goes for all you hipsters and Irony Girls, too. Stay home with your Jim Jarmusch box set. Or go watch a Tilda Swinton movie. Crummy movies belong to the masses, to the great unwashed, but not to you. Celebrities should keep their distance. Films like Sharknado succeed – to the extent that they succeed at all – because they are so cheesy and cheap. Indeed, one of the great things about bad shark movies is that the producers never have enough money to hire big stars, or can only raise enough money to pay for the stars to put in a few hours of shooting. In Deep Blue Sea, Samuel L Jackson checks out of the film early. In Sharknado, John Heard (Home Alone) is the closest thing to a star the film has. He doesn’t last long.

Films such as Sharknado work in part because famous people aren’t in them. In an ideal world, famous people wouldn’t even know that they exist. Clownish films are supposed to provide a refuge from celebrity, a place of sanctuary where ordinary people can enjoy themselves in peace without having Paris Hilton and Lady Gaga barge in and ruin everything.

In an era of Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter and The Good, the Bad, The Weird, it’s getting harder and harder to make a stupid movie for the ages. Sharknado beat the odds; it’s dumb beyond belief. But when the film’s producers went all postmodern and meta and started asking the public to come up with a title for the sequel, and when they started raising money to bankroll an extra-special chainsaw finale, it became clear that the bloom was off the rose and the thrill was gone. Just for the record, when the public was polled about the new film’s name, the best idea they could come up with was Sharknado II: The Second One. Seriously. Proving, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that Sharknado has officially jumped the shark.