Novelist Colson Whitehead, recipient of a MacArthur “genius” grant and a runner-up for the Pulitzer Prize, has devoted his latest novel to zombies. Is there a trend here? These days zombies are showing up in all the best places, including alternative versions of the genteel novels of Jane Austen. (I’m referring, of course, to Seth Grahame-Smith’s 2009 mash-up, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, which one of these days may be coming to a movie theatre near you.)

Whitehead, who’s usually more interested in the African-American experience and the history of New York, chose to depict a zombie-ridden apocalyptic future in his new Zone One. His choice isn’t entirely out of the blue when you realize he’s been having zombie nightmares ever since he saw Dawn of the Dead (zombies take over a shopping mall!) at age nine. In promoting his new novel, Whitehead released a list of classic films that have stoked his imagination. Kicking off that list is George Romero’s seminal zombie trilogy (Night of the Living Dead, Dawn of the Dead, and Day of the Dead), which Whitehead categorizes as “Sane Black Man Vs. The Crazy White People.”

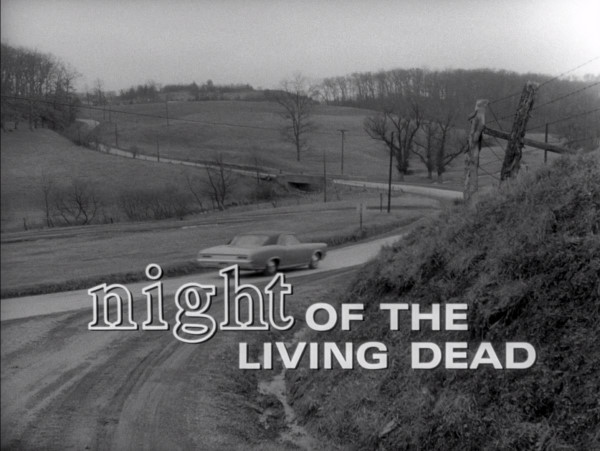

Whitehead’s focus on the racial aspect of Romero’s films isn’t inappropriate. In Night of the Living Dead, the last man standing in the war against the encroaching zombies is black. The 1968 film, made on a shoestring and shot in shaky black-and-white, centers on a Pennsylvania farmhouse where a cluster of locals seeks refuge from creatures who are literally blood-thirsty, and won’t take no for an answer. As the number of humans holed up in that farmhouse starts to dwindle, some become belligerent, and others weepy. Yet Duane Jones as Ben stays cool, bravely inventing stratagems to keep the monsters at bay. Ben’s skin-color is never mentioned, but it gives additional punch to the film’s shocking conclusion. When state troopers arrive at the farmhouse with guns and dogs to disperse the zombies once and for all, Ben is the only human being still alive. The troopers spot him in an upstairs window, quickly decide he’s one of “them,” and capably pick him off with a bullet to the brain, with one man congratulating another on his marksmanship.

Romero had never planned to make a movie about race. He cast an African-American as his hero because Duane Jones was the best actor who auditioned. But in the late Sixties, when the civil rights struggle was coming to a boil, the accidental resonance of this film could not be denied. Jason Zinoman’s article for Vanity Fair chronicles how on April 4, 1968, the print of Night of the Living Dead was sitting in the trunk of Romero’s Thunderbird convertible as he drove to New York to try selling his fledgling directorial effort to Columbia Pictures. Over the car radio came word that Martin Luther King had just been assassinated in Memphis. Though personally devastated by the news, Romero couldn’t help thinking, “Man, this is good for us.” King’s death convinced Romero of the timeliness of a film “whose defiant black hero fights off an army of the undead only to be gunned down by an all-white posse.” Americans already edgy about black-and-white tensions quickly picked up on the racial nuance.

This Halloween, we have a brand-new monument to Martin Luther King on our National Mall. But that’s not to say that all America’s racial problems have been solved. If Republican-leaning zombies start lurching toward the White House instead of a farmhouse, let’s hope Obama comes off better than poor Duane Jones.

By Beverly Gray Read Beverly’s Blog at http://beverlygray.blogspot.com